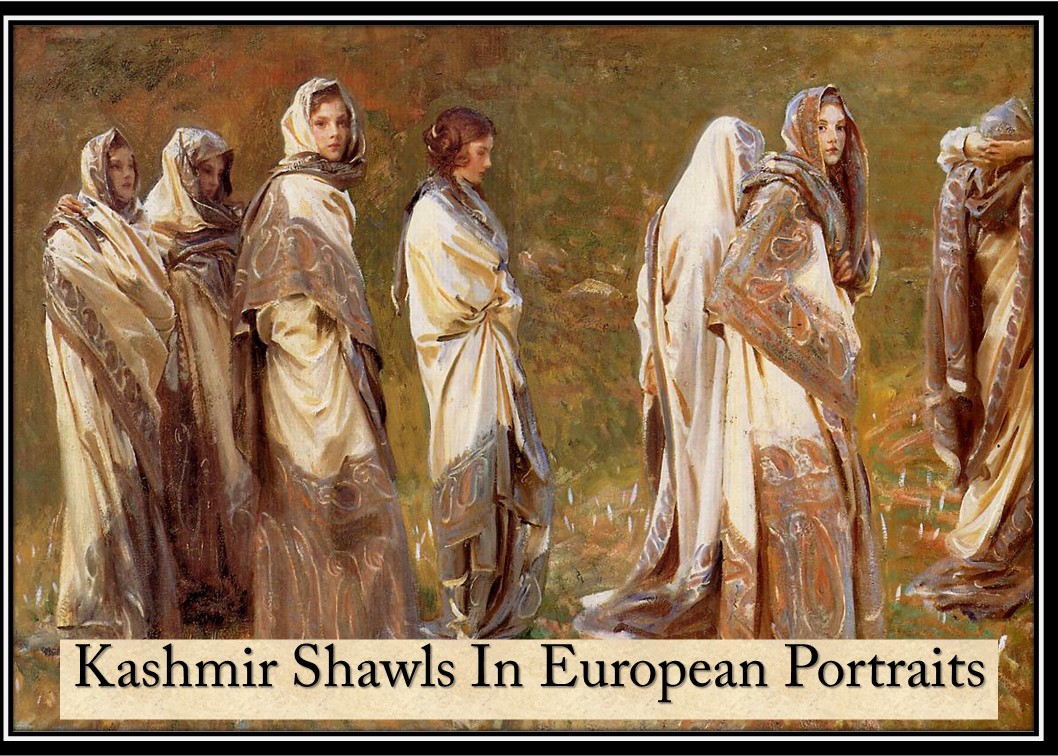

Kashmir Shawls In European Portraits

Over the 18th – 19th century, the Kashmiri Shawl occupied a unique place in European culture. That they were prized items is indicated by their prominent appearance in literature, portraits and even crime-reports in British papers of the time. One of the early reports, dating to 1776 promised a reward of 10 guineas on recovery!

In 1778, the above curious poem titled ‘The Shawl’ made its way to the Cumberland Pacquet, and Ware’s Whitehaven Advertiser. Nearly a century later, the shawl was still ‘a thing’, as evidenced by this romantic message published in The Times.

“Flo, thou voice of my heart, I am so lonely. I miss you more than ever. I look at your picture every night. I send you an Indian shawl to wrap round you while asleep after dinner. It will keep you warm, and you must fancy that my arms are round you. God bless you.”

Note: Kashmir refers to the place (anglicised versions: Cachmir, Cashemeer..and so on) Kashmiri is something from Kashmir Cashmere is the name given to the textile.

Over the years, the Kashmir Shawl has been the subject of scholarly study and research that looks at this enduring textile through multiple lenses: gender and identity, social status, colonisation, consumption & industry, to name a few.

In this first edition of our 2022 newsletter, we look at European portraits featuring the Kashmiri-shawl.

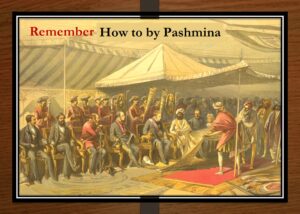

Shawls from Kashmir emerged in Britain, France and Russia around the same time – towards the end of the 18th century. One of the earliest visual records of the shawl worn by a European is believed to be a portrait of Captain John Foote by Joshua Reynolds (1760). In the portrait, the Shawl is tied around his waist like a belt. These shawls had typically been worn by men of rank in India; by the 1770s, European & British merchants were shipping these home, sometimes as gifts.

With Capt. John Foote fashioning himself as an Indian ‘nabob’ (by this time, the word had come to signify men who had returned from the East, having made a fortune there) in the portrait, what message did it convey? Historians read the portrait as an act of self-elevation – with an aim of gaining acceptance into the elite British society. The East India Company Army was different from the British Army, and on home-soil the difference in military status was stark. Another portrait by Reynolds of Mrs. Horton, known for her scandalous relationships with the political elite prompted visual culture experts to discuss the shawl’s representations and its association with the exotic east & its ‘promiscuity’ (like the imagined harems!).

So how did the shawl become a “status symbol” ?

Political changes in the 18th century were well-reflected in the fashion trends of the time. In England, William Hastings, the Governor General of Bengal, along with a few others sought to “reconcile” the British with Indian culture. By 1784, The Royal Asiatick Society of Bengal was established, towards the pursuit of knowledge of India’s classical past. A rise in orientalism, now positioned the wearer of an Indian shawl as an “aesthete”.

Emma Hart (later, Lady Hamilton), A Fashion Icon in the 1780s: Britain, France and Kashmiri shawl

Emma Hart came to be known in London’s upper society through the painter George Romney’s portraits of her. Her rise from her humble origins to ‘Lady Hamilton’ is a fascinating story in itself, though for now, we’ll focus on her act that had fascinated European society. Emma Hart became ‘Lady Hamilton’ through her association with Sir William Hamilton, British Ambassador to the Kingdom of Naples. She combined her earlier experience in theatre, with Sir William’s taste in visual art to create a series called “Attitudes”. These were short, 10-minute performances imitating classical sculptures through mime, draping and gestures. The cashmere shawls were an important prop in these performances held for private audiences as early as 1787.

These acts, covered by the Press and in portraits, celebrated the Kashmiri Shawl’s elegance.

Meanwhile, during the French Revolution, the cashmere shawl became an ideal accessory for women.

The Revolution was against the aristocratic elite and looking the part overtly was not the best idea. Aristocratic women then, adopted the Indian chint, and other items of clothing that demonstrated the value of “simple yet luxurious”. The muslin gown with a Kashmiri Shawl to go with it, was a perfect choice.

The Cashmere Fever

German cultural critic Walter Benjamin’s masterpiece “The Arcade Project” was a treatise on shopping in 19th century France – and a refreshing take on recording the times. It gave insights on the cultural consequences of capitalism through combining different commentaries on Paris. In his work, he acknowledged the cashmere shawl as an essential commodity of the early to mid 19th century. Quoting an 1854 volume titled Paris chez soi, he writes:

“… In 1798 and 1799, the Egyptian campaign lent frightful importance to the fashion for shawls. Some generals in the expeditionary army, taking advantage of the proximity of India, sent home shawls … of cashmere to their wives and lady friends … From then on, the disease that might be called cashmere fever took on significant proportions. It began to spread during the Consulate, grew greater under the Empire, became gigantic during the Restoration, reached colossal size under the July Monarchy, and has finally assumed Sphinx-like dimensions since the February Revolution of 1848”

Napoleon is said to have gifted shawls to both his wives; the Empress Josephine became known for her collection of over 200 of these!

Not without my Shawl : Aristocratic women, the Cashmere & Fashion Plates.

The Empress Joséphine went a step ahead, using shawls as dresses, giving rise to a new trend. In the 1770s, The Lady’s Magazine had become one of the first distributors of fashion-plates in magazines. The National Portrait Gallery (NPG, UK) records the growth of women’s fashion periodicals during this time; these anticipated new styles as well as recorded what had been worn, much like our fashion magazines today. The shawl-as-a-dress trend in the beginning of the 19th century picked up rather speedily through these. In 1808, the Bells Messenger Weekly included the Indian Shawl as one of the ‘most Elegant & Select Fashions for the Season’ alongside the French Cloak.

Daniel Saint’s Lady with a Greyhound, 1839-42

Daniel Saint was known for the official portraits he created of Napoleon and his court’s members. This particular watercolor painting, around 12in x 7in is a feat in terms of the detailing it achieves.

Alfred Stevens (1823-1906)

The paintings by 19th century Belgian painter, Alfred Stevens are our favorite! As you will see, he includes the Kashmir shawl in most of his paintings. A catalogue accompanying an exhibition on Stevens’ work at the Van Gogh Museum states: When the painter settles in Paris, he concentrates on the representation of ‘women of the upper class’. He almost exclusively focuses on one subject: Parisian women of the Second Empire and later of the Third Republic. Situated in the melancholic atmosphere of lavish salons and boudoirs, he elucidates rich women’s experience of loneliness and the shallowness and futility of 19th Century bourgeois salons. His keen sense of observation induces art critics to define him as ‘the chronicler of the fashionable world’

The Kashmir Shawl Vs the ‘Paisley’ Shawl & Norwich Shawl.

“If you wish to judge of an Indian shawl, shut your eyes and feel it; the touch is the test of a good one.”

Fanny Parkes, Begums, Thugs and White Mughals: The Journals of Fanny Parkes., ed. William Dalrymple

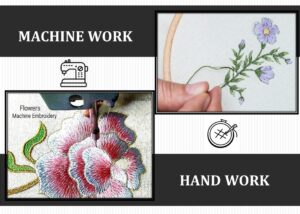

By the time Fanny Parkes’ journal records the Kashmir-shawl (1835), it had already become a popular fashion item. The Jacquard loom (introduced in the 1820s) made it easier to produce shawls in larger quantities and imitation shawls manufactured in Norwich and Scotland made their way into the market. In Paisley, the industry worked in collaboration with agents in Kashmir to source designs to imitate.With the Industrial Revolution combined with Britain’s imperialist ambitions, the exquisite shawl came to be appropriated (just like Chint). Queen Victoria (pictured below), though in possession of the exquisite Kashmir-made shawls, preferred to wear the British manufactured shawls in public as an endorsement of the local industry.

The Great Exhibition of 1851 not only showcased handwoven shawls of Kashmir, but also the ones made in Norwich and other parts of Europe. The Norwich shawls were praised for their likeness to the Indian shawl, and better in quality than the Paisley-manufactured ones, became quickly accessible to women outside aristocratic circles.

Kashmiri Shawls, from Amritsar, in France…

In 1813, Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s conquest of Kashmir and his interest in the shawls led to a revival of the industry hit by natural calamity. The Sikh Maharaja had recruited two members of Napoleon’s army, Jean-Francois Allard and Jean-Baptiste Ventura — as his Generals. By 1835, the Generals were exporting shawls to Europe, and Amritsar had become the centre of the Kashmiri shawl trade. Writing in 1872, Baden Powell noted that shawls from Amritsar were closest to the ‘excellence’ (quality) of Kashmir-made shawls.

The Kashmiri Shawl : no longer a trend?

Centuries later, the Cashmere shawl is still sought after and continues to be part of a luxury bouquet. Paintings by John Singer Sargent evoke the sophistication and elegance that this timeless craft represents.

A thing of beauty is a joy for ever:

Its loveliness increases; it will never

Pass into nothingness; but still will keep

A bower quiet for us, and a sleep

Full of sweet dreams, and health, and quiet breathing.

Please call our Customer Care for any query. (9am to 6pm) +91 9463 777 888 or write @ info@albasir.in.

LAST UPDATED: 24-04-2024, By SHAFIA