RAFUGAR: The Beautiful Art Of Restoration

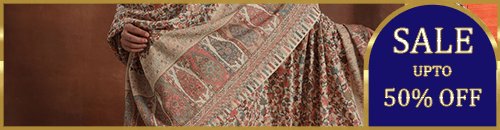

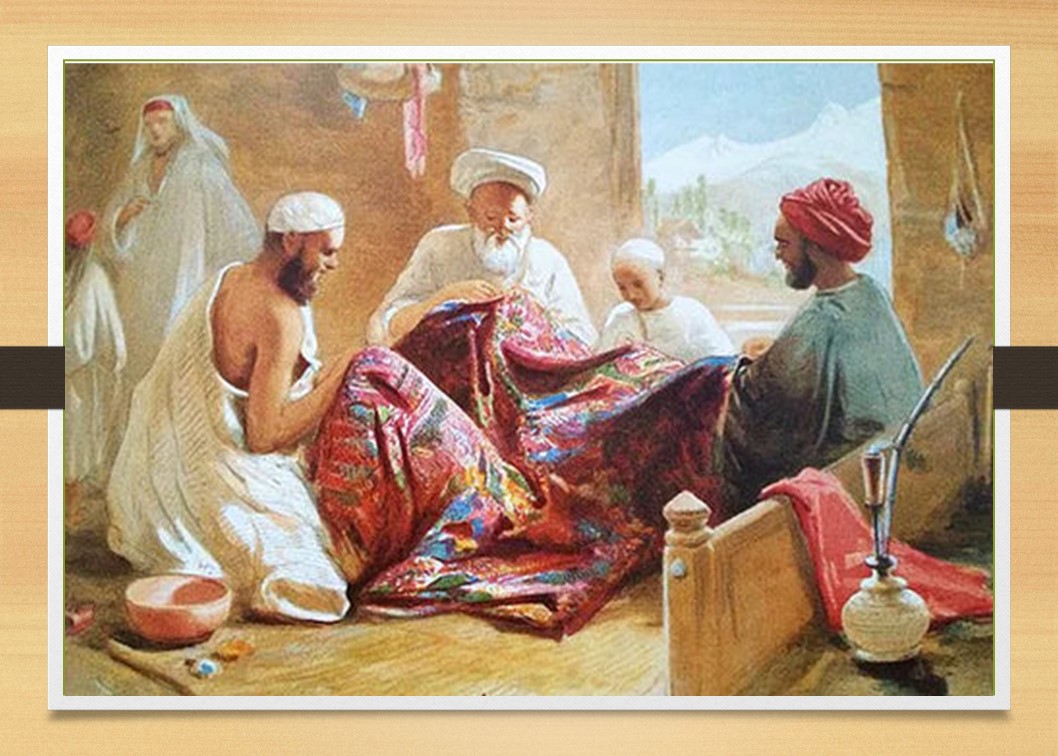

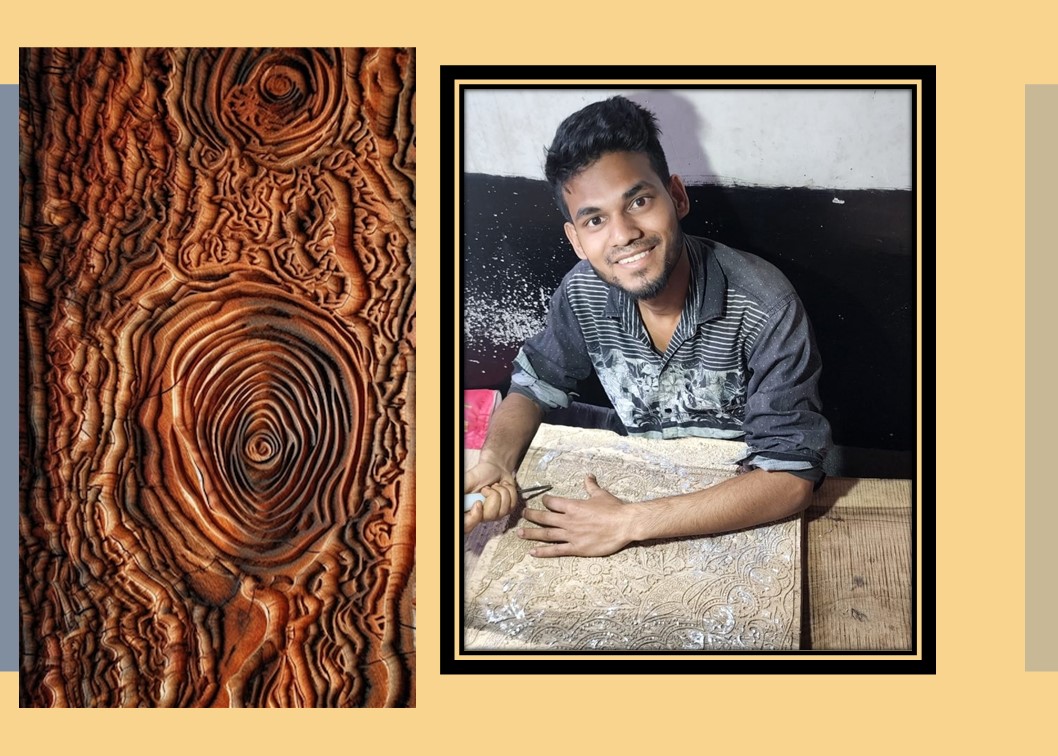

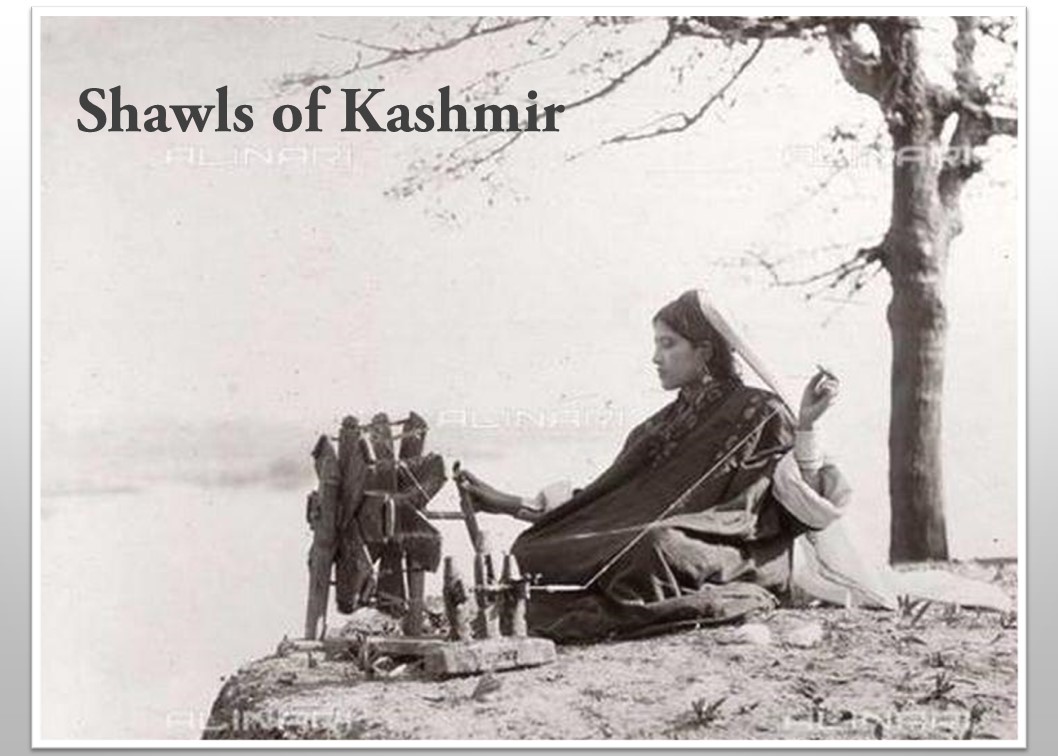

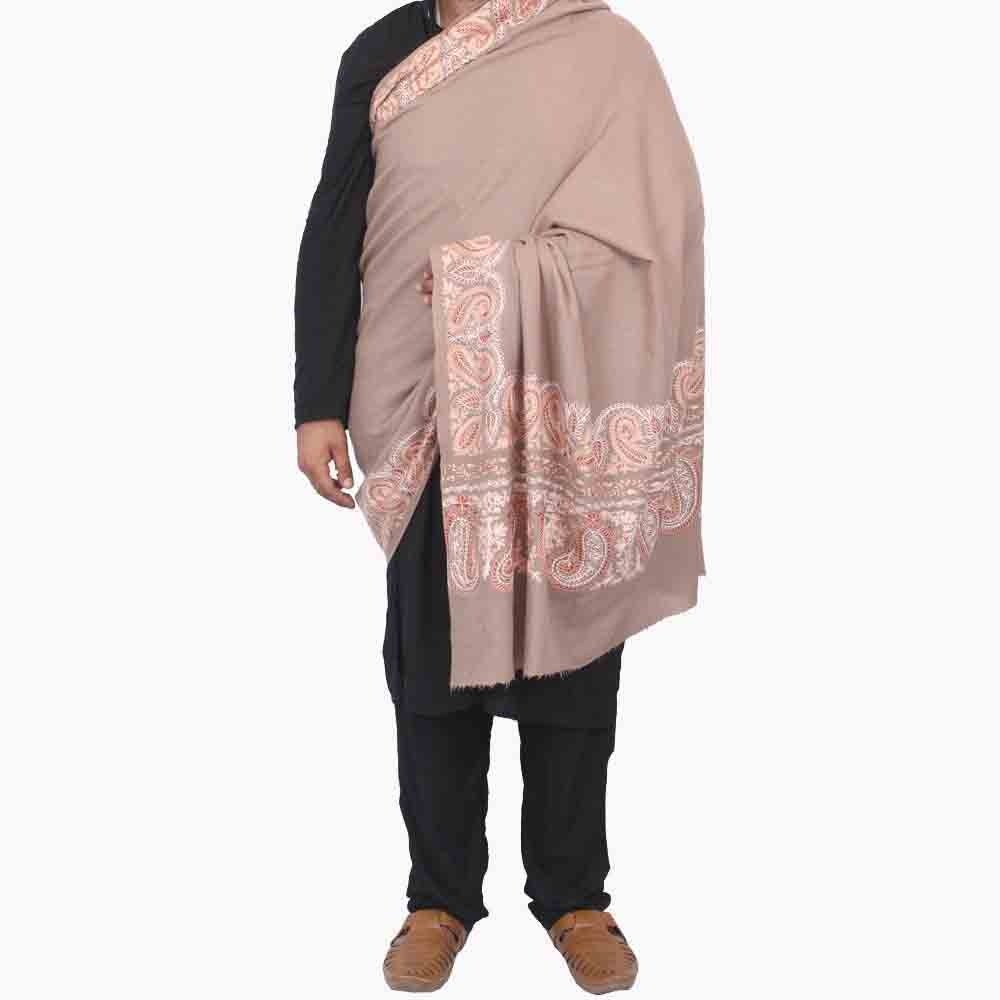

What do you do with a shawl that has been in your family for a long time, costs more than 1 lakh, and suddenly you find a slight cut or moth damaging the precious fabric. One cannot just discard the shawl that has a huge sentimental value to it, nor can keeping it as it is increasing the risk to damage. It is at this time a Rafugar – one who darns – comes to your rescue, who can be aptly described as a doctor of shawls. Bring a damaged shawl or any fabric to him and he will hand it back to you in almost original condition. “A high end Shawl costs lakhs of rupees. Many a time the Shawl has been in the family heirloom for generations, thus becoming a treasure or sort. Such a shawl is a thing of pride and if anything happens to it, one cannot simply throw it away or buy a new one. These damaged Shawls are brought to us and we mend them,” said Mohammed Salim Bhat a Rafugar from Ellahibagh, Srinagar. “We study the shawl, its pattern, color etc., and then mark our boundaries to start the work. We match the thread and finish the product in a way that it is hard to find any traces of repair. ”A saying is popular among Kashmiri expert Rafugars that only Almighty and they alone can identify where a fabric has been repaired. Darning has an interesting story in Kashmir which made it flourish. As everything is linked with politics here, darning too started as a result of policies of government.

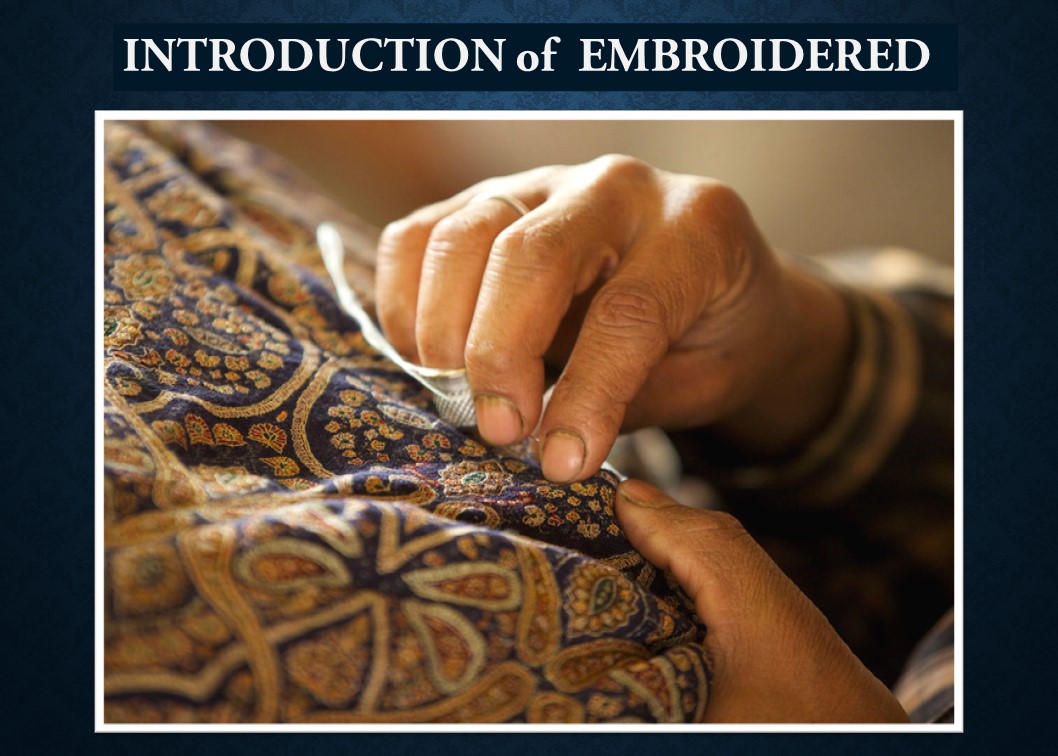

“During the Afghan rule, the Governors imposed heavy tax on Shawl manufacturing through the infamous Dagh Shawl department. Their officials taxed the Shawls based on the size. To evade the taxation the Kashmiri artisans started to make shawls half that size. Later the two, or more pieces were joined together skillfully by a darner,” said Salim Beg, State Convener INTACH. “The Shawl was made of full size without paying tax thanks to these rafughars for the joining work they accomplished. Such was the skill that one couldn’t find the joint through naked eye.” As more artisans came to know of the trick, the practice became widespread and rafughars became most sought after. It was for a long time before Afghan Governors realized the scam. The second time when these Rafughars came to rescue of the Shawl industry was in early 19th century, when an Armenian trader Khawaja Yusuf along with native darner Ali Baba introduced Amlikar (embroidered) shawls. Yusuf had been deputed to Kashmir in 1803 as the agent of a Constantinople trading firm. The duo produced the first needle-worked imitations for the market at one-third of the cost of the loom-woven shawls. It helped in enormous saving in production costs and the needle-worked shawls at first escaped the Government duty levied on the loom woven shawl, which in 1823 amounted to 26 per cent of the value.

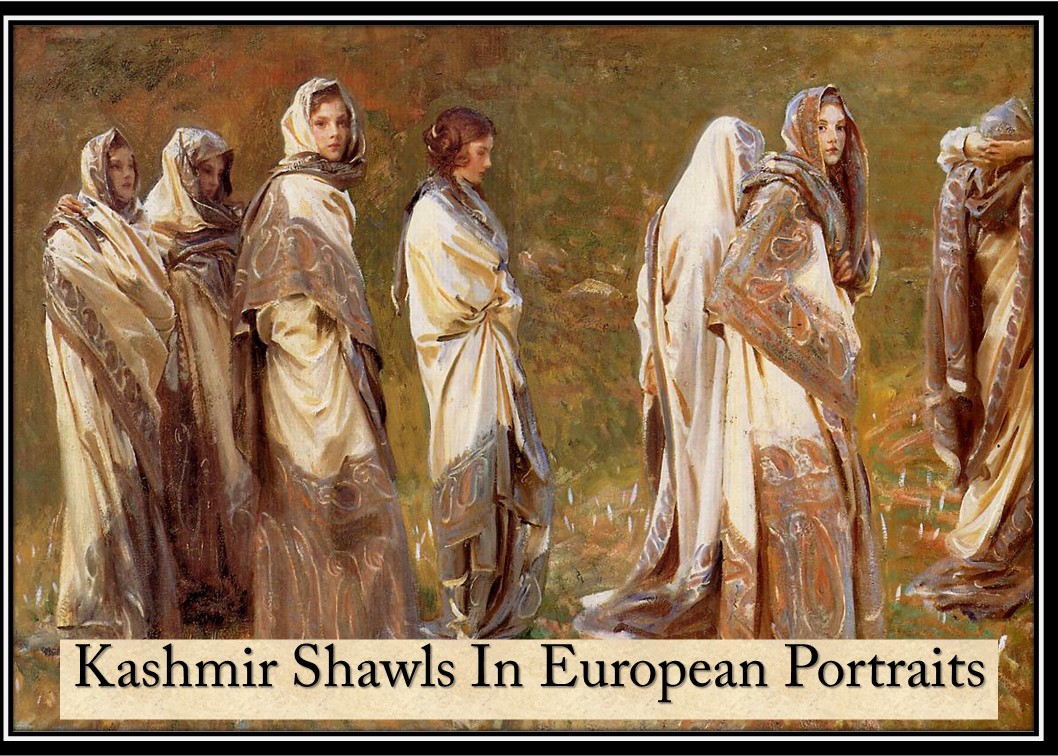

Traders made enormous profits, and this branch of the industry expanded rapidly. In 1803 there were only a few rafugars or embroiderers available with the necessary skill for the work. Twenty years later, there were estimated to be five thousand, may of them having been drawn from the ranks of former landholders, dispossessed of their property by Ranjit Singh in 1819, when Kashmir was invaded and annexed to the Sikh kingdom. Moorcroft has described in his book that as many as eight looms being engaged on a single shawl; but later in the 19th century this number was often exceeded, and there was one report of a shawl being assembled from 1,500 separate pieces. Mary M Dusenbury and Carol Beer in their book ‘Flowers, Dragons and Pine Trees: Asian Textiles in the Spencer Museum of Art’ writes “Assembling a shawl from eve eight segments required considerable skill on the part designers and weavers to assure that the patterns and sizes fit together. Shawls composed of hundreds of small pieces, dating mostly to the third quarter of the nineteenth century, required astonishing skill to assemble into a coherent unit.

The craftsmen responsible for this was were the rafugar, needleworkers who received the individually woven segments of a shawl and joined them together like a jigsaw puzzle with such skill that the seams are very difficult to detect. The rafugar also embellished the design as necessary to make the parts work together as a whole. They worked in a technique closely allied to Kani weaving so that their work was well integrated with that of the weavers. The tradition continued as the trade expanded. However as the oppressive taxation was eliminated from the system, the need of rafugars also decreased. There were other reasons too that led to the downfall of this art form. Rafugars are often seen a lower class in the prime Shawl making industry. It is an irony that the people who manage to impart invisible joints on a Shawl want to remain invisible. “People love to call themselves Shawl makers instead of rafugars as the former is glamorous and commands more respect in Kashmir and outside,” said a rafugar. “Due to the name tag, even the younger generation is not coming forward to adopt the job. The second thing that led to is downfall is that the expert rafugars refuse to train new people as they are extremely secretive of this art.” Ironically the decrease in number of rafugars has come at a time when the demand for the work is increasing manifold. “These are tens of thousands of shawls in family heirlooms in different States of India. Even if only one percent of those shawls needs repair or conservation, it is a huge market which only Kashmiri rafugars can cater to,” said Beg. “We at ALBASIR usually get number of requests from people around the country for help to restore the shawls and we find it difficult to find the skilful person here.” An official from the Handicraft department said that earlier during Maharaja’s time Kashmiri people knew 56 skills but today only 26 skills have survived and one among these 26 is Rafugari which is dying a slow death. He said the number of Rafugar’s has declined from last 30 to 40 years which has become a cause of concern for the government, and added that none has been applying for Darner’s or Craft instructor post in Handicraft’s Department resulting in posts lying vacant from years.

Unable to find master trainers here, the organisers had to bring experts from Najibabad, which is a hub of Rafugiri in UP to train the locals. According to Salim, who is one of the rare younger generation Rafugars, there are only around five to six highly expert rafugars in Kashmir. “I have been in this trade for around 27 years and I took up needle when I was just six years old. It is a continuous process and one needs to update the knowledge with the every passing day.

As we get newer types of fabrics we have to improvise to mend them too,” said Salim, whose family for many generations has been in this art. In the shawl making industry it is often said that Rafugars make more money than other shawl artisans. “I have shawl manufacturing firm with 30 looms. A weaver earns around Rs 10000 per shawl, which he completes in around a month. On the other hand a rafugar can earn that much in just ten days or less,” said Shabir Ahmad. “Whenever I have a defect in any shawl I turn to a rafugar and he charges anywhere Rs 1000 to 5000 to mend the defect which takes just at the maximum two to three days.” These days the Rafugars not only mend shawls but phirans, costly shirts, coats or even jeans. At the workshop a Rafugar had the order worth Rs 30000 for repairing a Sari from an outside customer. Beg says that the art form has huge potential in providing livelihood to people. “Conservation and restoration of old artefacts is a huge industry and one can make huge amount of money,” said Beg. “This workshop will go a long way in helping this art form.

Women

Women Home & Living

Home & Living